- Managing your Practice

-

- Your Benefits

-

Introducing the ultimate Club MD experience

From work to play, and everything in between, we provide you with access to hundreds of deals from recognizable, best-in-class brands, elevating every facet of your life – from practice supports to entertainment, restaurants, electronics, travel, health and wellness, and more. Your Club MD membership ensures that these deals are exclusive to you, eliminating the need to search or negotiate.

Welcome to the ultimate Club MD experience. Your membership, your choices, your journey.

-

- Advocacy & Policy

-

- Collaboration

- News & Events

-

Stay Informed

Stay up to date with important information that impacts the profession and your practice. Doctors of BC provides a range of newsletters that target areas of interest to you.

Subscribe to the President's Letter

Subscribe to Newsletters

-

- About Us

-

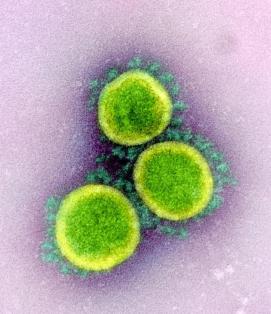

Remembering lessons from the “Summers of polio” in the time of COVID-19

May 15, 2020

President's Blog

“Necessity is the Mother of Invention” - Plato

Human history is full of examples of an acute crisis causing seismic changes in health care, social interactions, business practices, and government structures. There can be no question that the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 will be considered one of those transformative milestones.

Consider the summers when polio ravaged Canada, peaking here in 1953. Like COVID-19, polio was an invisible offender, spreading easily from person to person. In polio’s case, that spread was largely due to poor hygiene. While the majority of infections were mild, the virus spread easily because people didn’t recognize they were ill. Just 1-2% of the population developed motor cell disease in the spinal cord or brain, but their symptoms were severe, including paralysis. These acute cases overwhelmed healthcare systems at times.

As a nation, and indeed globally, we rapidly adapted to limit the cases of this devastating disease across the “summers of polio”. Pools and parks closed. Vacations were cancelled. Public gatherings were limited. Physical and social distancing measures where implemented and good hygiene practices were emphasized to limit the spread. Families were devastated by both the disease itself, and the change in societal practices. Parents eyed children playing with their own children with suspicion and anxiety. The psychological and financial impacts of families losing children or parents being unable to work or participate in household care lasted decades beyond the implementation of a vaccine.

Adapting and reinventing ourselves in a crisis

As with other public health crises in history, we adapted and invented. The practice of medicine needed to adapt quickly to the use of the Iron Lung and Rocking Beds, first developed in 1927 by Harvard’s Philip Drinker and Lewis Agassiz Shaw Jr. These negative pressure apparatuses relied on the movement of the diaphragm to exhale, passively allowing ventilation. Despite being cumbersome and expensive in that time, they were quickly adopted.

Medicine then had to learn how to manage the physical consequences of limb paralysis, and the consequences of being confined to the mechanical respiration equipment. The medical community learned much about the importance of keeping the body moving, even when the patient can not voluntarily move. Physical therapy practices evolved and expanded to include many measures we use today in our Intensive and High Acuity units today. Respiration could be supported at home. Families separated by polio could return home to live out their lives, rather than being confined to a hospital.

The advent of the Salk Vaccine in 1955 and the Sabin in 1962 allowed Canada to gain some control over the virus, but the nation was not declared polio-free until 1994. For more than 30 years, organizations such as Rotary International’s Polio Plus Program have continued their volunteer efforts globally to vaccinate more than 2 billion children, garnering the support of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Although I have highlighted polio in this blog, I could have picked any number of other diseases, including Diphtheria paralysis, to demonstrate our history.

Learnings from yesterday makes us stronger today

Here in BC, we have turned the corner in Wave 1 of the SARS-Cov2 pandemic. Many of the measures introduced are the same as those used to combat polio. Our medical community has come together as a profession to innovate, share learnings, and adapt in a rapid and nimble way unprecedented in our careers. Collaboration with governing bodies and communities to co-design and rapidly adopt best practice measures has been successful. Innovation plays a key part.

In the 1950s, we saw the invention of the iron lung. Today, we are transitioning to virtual care to provide medical treatment in a way that keeps everyone safe. We are having transparent and honest discussions around our limited resources, and co-developing best practices to extend the services we needed to deal with the disease surge. The way we have responded to this health care crisis will change the way we design our healthcare system and in some ways, the way we practice in the future. These conversations continue as we ramp up our elective healthcare services.

Time to pause and reflect on our “new normal”

We are now able to pause, take a deep breath, and begin to reflect on SARS-CoV2. As we look for what worked best and what practices should become our “new normal” for standard of care, I wonder what will be highlighted in decades to come?

We are now able to pause, take a deep breath, and begin to reflect on SARS-CoV2. As we look for what worked best and what practices should become our “new normal” for standard of care, I wonder what will be highlighted in decades to come?

Will we remember this as the time that our tolerance for ER overcrowding and hallway beds ended? Will this become the time that everyone becomes attached to a primary care medical home via the increased capacity made possible by virtual and team-based care? Will this be the time that the physician voice in how we assign and manage our limited healthcare resources rises to the top with our governing bodies?

Whatever your personal learnings and reflections may be, I do encourage you to share and collaborate with all parties in all venues. We have made it over the first wave hump. We will need your knowledge and experience to manage the second wave imminently, and the third wave of many other medical conditions in the years ahead.

Thank you for your dedication and ongoing commitment.

- Dr Kathleen Ross